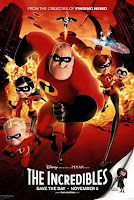

Paul O'Brien, one of my favorite cultural bloggers, in his review of Ratatouille commented that the Brad Bird's two Pixar films are essentially a celebration of "well-founded elitism." The argument goes something like this: both The Incredibles and Ratatouille are about what can be described as supernaturally gifted people/animals that should not be ashamed of their gifts that they've been given and "true excellence should be celebrated."

All of that is certainly an interesting view of things, but I also can't help but think it is also a bit short-sighted. Yes, both Remy the Rat and the Parr family are displayed as being exceptional. But they also aren't shown as being perfect, or necessarily better than anyone else. The Parrs especially are shown as being jealous, self-obsessed and otherwise human throughout the film. Yes, they are heroes, and yes, in the end they do the right thing. But to say that they are elite or in some way elevated from common people seems to miss the point somewhat.

The Incredibles' core is about not merely taking charge of those exceptional qualities, but using those gifts towards bettering the world. To use the classic Stan Lee axiom, the Parrs learn that with great power, great responsibility isn't far behind. When Mr. Incredible sees victimization, he can't help but think that he should do something. There is a core somewhere in him, beneath that narcissistic streak (his own elitist tendencies) is a person called to selfless service of the world. Within the model of the superhero, Mr. Incredible serves as an example of doing the right thing with the ability you've been given.

While Ratatouille is certainly less flashy than Incredibles, it is no less prophetic in its charge to better the world in any way that you can. Remy the Rat is a gifted chef, due to his amazing sense of smell and taste. He is also an outcast; his rattiness causes him to be a reject due to his refined tastes not exactly being appreciated within his clan. So like many artists, he has to find his own place in the world, and figure out a way to express himself somehow, a wanderer without a home.

He finds his soul mate in Alfredo Linguini, the nervous but well-intentioned garbage boy who also has no family any more. Alfredo, who has no skill in cooking (like most of us, I'd assume) , needs a job, and has his last chance in the kitchen of the late Gusteau. Soon, a symbiotic relationship is created: Remy gets a home and gets to do his favorite thing and cook, Alfredo keeps his job and starts to get some fame. Remy and Alfredo help each other, and in the kitchen Remy quite literally moves Alfredo, reflecting the way some believe that people are "moved" by the spirit. Remy serves as a guide to Alfredo's hand, helping him to make excellent food for people.

But haute cuisine is really an elitist skill, isn't it? There is certainly a celebration of foodyism throughout the film, as well as a not so subtle condemnation of mass-produced frozen food. But what is more life-affirming, to say nothing of life-giving than food? It is one of the staples of human existence and community; there are several scenes throughout the film, including one prodigal sonesque party among the rats upon Remy's return that show the gathering of people around food; it is what initially binds Remy and Alfredo together.

As if to make the point, the film ends with the heartless Anton Ego being fed "peasant food," the titular dish. Instead of taking notes and critiquing the meal, he has a flashback to his childhood and how his soul would be lifted when his mother fed him. Food binds us, makes us human and keeps us alive. Remy's skill is feeding people, which is one of the things that Christ calls people to do: feed the hungry. Ratatouille may never feed the physically hungry, but he sees a hunger and emptiness in Anton Ego that needs to be fed as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment